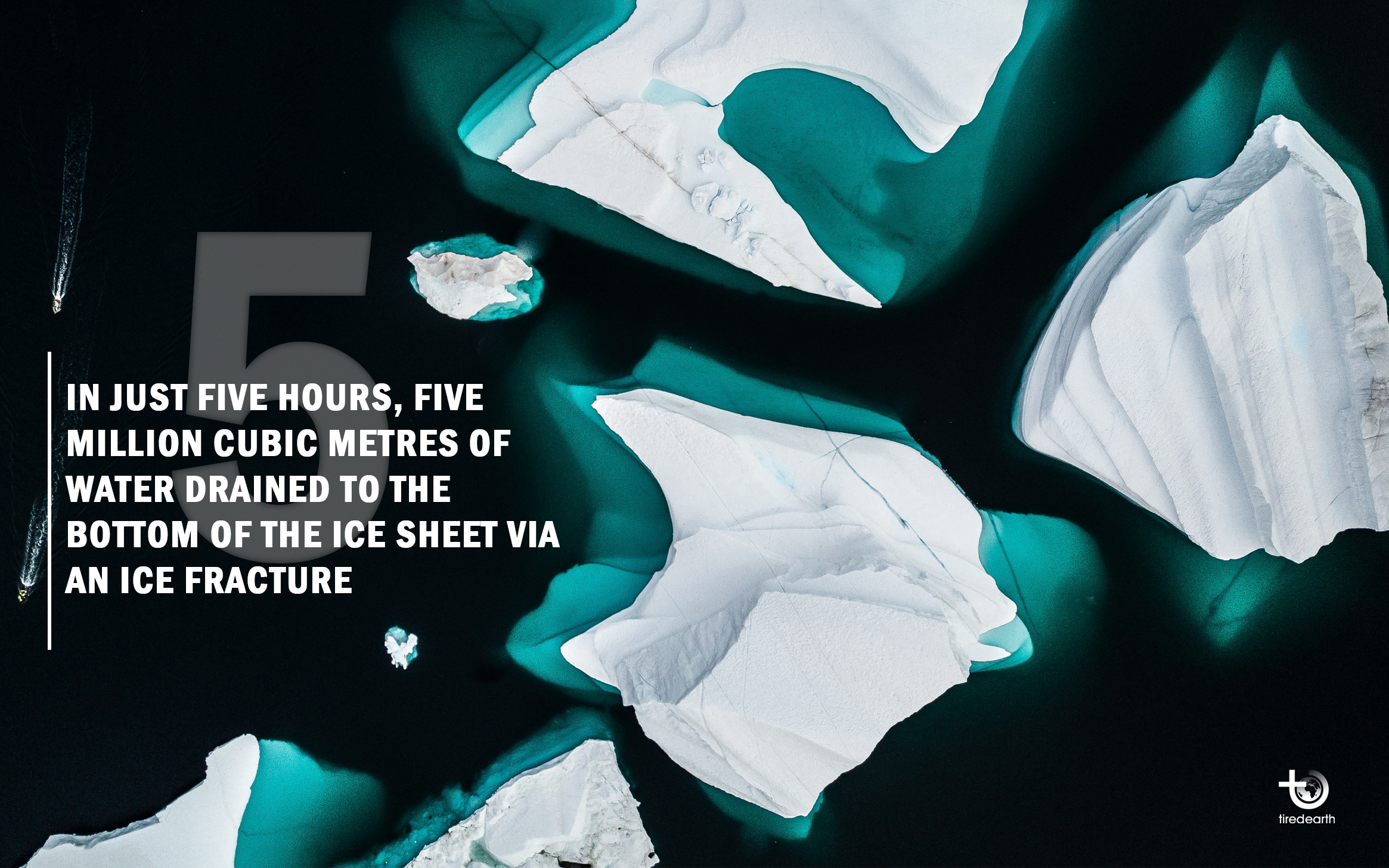

Each summer, thousands of lakes form on the Greenland Ice Sheet as the weather warms. Many of these lakes can drain in just a few hours, creating caverns known as moulins, through which water descends to the bottom of the ice sheet. These cavities typically stay open for the remainder of the melt season, as meltwater from streams and rivers on the surface descends beneath the ice. Given that the ice sheet is typically a kilometre thick or more, the flow of water into the moulins may well be the world's largest waterfalls.

Unexpected consequences of sea level rising

Ice slabs have already caused Greenland’s runoff zone to expand by about 26 percent, according to the new study. So far the additional runoff has only added about a millimeter to global sea levels. Greenland now contributes a little under a millimeter per year to rising sea levels, through a combination of icebergs breaking off glaciers and melt occurring at the surface and base of the ice sheet.

But if Greenland’s surface hardens more, runoff could rise dramatically. Under a worst-case scenario where carbon emissions continue to climb until the end of the century, the researchers calculated that ice slab proliferation could add up to 3 inches of sea level rise by 2100, boosting the ice sheet’s overall sea level rise contribution by nearly a third. In both a middle-of-the-road scenario where emissions peak by mid-century and the high emissions one, the amount of runoff from Greenland’s interior roughly doubles by century’s end.

The new study raises questions about a finding contained in the most recent report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which found that surface meltwater is unlikely to be causing significant enough alterations to the flow of the ice sheet. Specifically, the study found that satellite measurements being fed into computer models probably significantly underestimate the amount of rapidly draining meltwater lakes on the ice sheet, especially lakes that partially drain.

Comment

Reply