41 years after the most tragic industrial disaster in history, the victims have been forgotten, the perpetrators remain unprosecuted under a system of judicial immunity, and toxic, hazardous

Attention: This article contains content or images that may be considered disturbing or inappropriate for some audiences!

"Around 12:30 AM, I was awakened by the sound of my child's cough. In the dim light, I saw that the room was filled with white smoke. I heard numerous screams. They were shouting, 'Run!' Then I started coughing, as if I were inhaling flames. My eyes were burning."

These are the words of Aziza Sultan, a survivor of the horrific tragedy caused by the toxic gas leak at the american Union Carbide’s pesticide plant in Bhopal. Over forty years after the disaster, it continues to claim lives and contaminate both water and soil. But why did this disaster occur? Why did the American company Union Carbide fail to take responsibility for the negligence that led to the incident, and why have the pollutants from this catastrophe not been properly cleaned up?

The body of an unidentified girl who died in a methyl isocyanate leak. Photographer Pablo Bartolomeo's photograph, taken in Bhopal on December 4, 1984, won the World Press Photo of the Year award and became one of the symbols of the disaster. Photo: worldpressphoto.org

The Shadow of Death

On the night of 2–3 December 1984 a cloud of methyl isocyanate (MIC) drifted from the pesticide plant of Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) into the sleeping city of Bhopal. Thousands died almost immediately and many tens of thousands were injured; official figures record at least 3,787 deaths. In addition, a government affidavit from 2006 estimated injuries numbering 558,125 — including tens of thousands of temporary partial injuries and several thousand permanent disabling injuries. Beyond these acute casualties, roughly half a million people surviving the initial exposure developed chronic health problems: respiratory illnesses, blindness or eye damage, neurological disorders, skin and organ damage, and other long-term morbidities. generations since have reported chronic disease and contamination around the site. Yet, despite a 1989 settlement and later criminal prosecutions of Indian managers, full corporate responsibility—financial, criminal and moral—remains fiercely disputed.

Bags containing the skulls of those killed in the Bhopal gas disaster were kept in the pantry of Hamidiya Hospital after the autopsy, and were found by photographer Raghu Rai. Photo: bhopal.net

The Ongoing, Invisible Disaster

But the catastrophe did not end with the gas. After the plant’s closure, enormous quantities of chemical waste — pesticides, solvents, heavy metals, organochlorines, and other toxic by-products — were abandoned on-site or stored in evaporation ponds and waste pits. Because these wastes were not properly disposed of, rainwater and natural groundwater movement caused leaching: toxins seeped into the soil and infiltrated the aquifers supplying drinking water to nearby communities.

Multiple studies over the decades documented this contamination: for example, water and soil samples taken even 3 km from the former plant show high concentrations of pesticides and heavy metals — sometimes dozens of times above safe limits.

The polluted groundwater has remained a primary drinking-water source for tens of thousands of people, often in low-income neighbourhoods.

As a result, many inhabitants — including children born years after the disaster — suffer persistent health problems, congenital disorders, birth defects, and other chronic illnesses. Campaigners and independent researchers describe this chemical contamination as a “second disaster.”

Forty Years of Toxic Abandonment

For more than forty years, the toxic remains of the Union Carbide pesticide plant have been left virtually untouched, even though they continue to leach poisonous chemicals into Bhopal’s soil and groundwater. Despite repeated demands from victims’ groups, Indian authorities, and international NGOs, the American parent company Union Carbide — later acquired by Dow Chemical — has consistently distanced itself from responsibility, arguing that it has no legal obligation to clean up the abandoned factory site or collect the thousands of tonnes of hazardous waste left behind. As a result, the rusting structures, contaminated soil, and pits filled with pesticides and heavy metals have never undergone a comprehensive decontamination process, turning the area into a permanent toxic hotspot where dangerous pollutants continue to spread into nearby neighbourhoods. This prolonged inaction represents one of the clearest examples of corporate evasion and environmental injustice in modern industrial history.

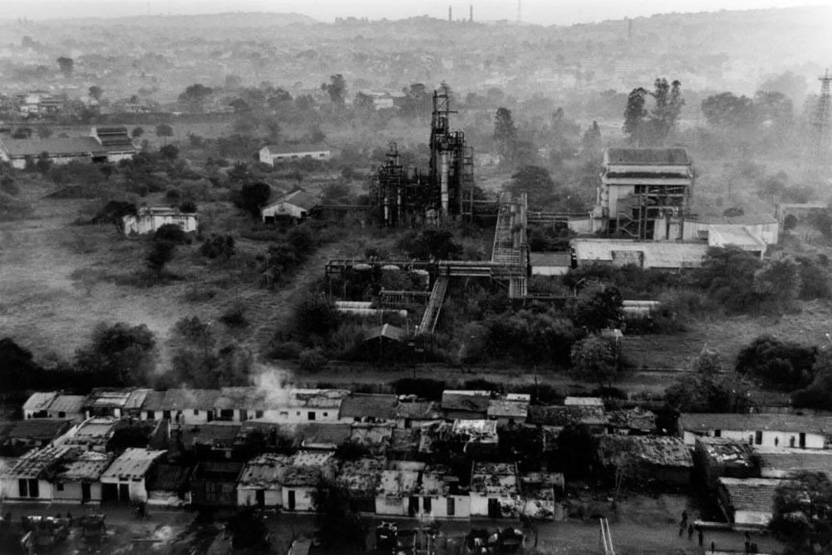

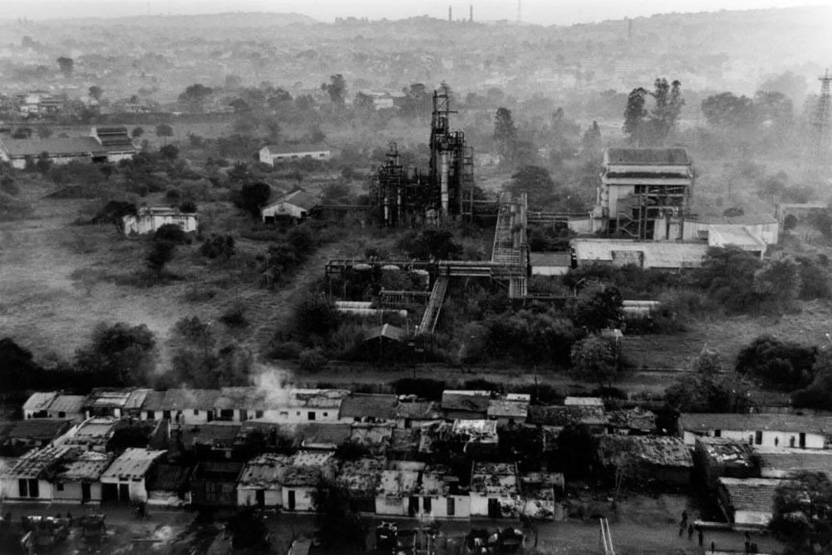

Children play in front of the Union Carbide factory in Bhopal on November 18, 2009. According to experts, approximately 25 tons of toxic materials still remain at the site.

Blame, sabotage claims and shifting narratives

Beyond courtroom tactics, Union Carbide advanced alternative explanations for the disaster—most notably the claim that an act of sabotage or deliberate tampering precipitated the MIC release. Company-commissioned reports and subsequent statements suggested that water had been introduced into MIC storage by an employee or an act of foul play. Those narratives served two functions: they provided a proximate cause that would point to local actors rather than corporate management failures, and they complicated the causal story needed to establish gross negligence by the parent company. Independent investigators and later academic reviews, however, documented numerous safety failures at the plant—malfunctioning relief systems, inactive alarms, understaffing and deferred maintenance—that undercut the sabotage claim as a complete explanation. The contest over causation thus became a contest over responsibility.

Political influence, failed extradition and criminal accountability

When it came to criminal accountability, efforts to hold senior UCC executives to account stalled. Warren Anderson, UCC’s chairman at the time, was arrested briefly on arrival in Bhopal in December 1984 but was soon released and returned to the United States; repeated demands for his extradition failed, citing insufficient evidence and diplomatic complications. The practical difficulty of extraditing a foreign CEO, combined with the legal settlement on civil claims and the focus on prosecuting on-the-ground managers in India, meant that the highest-level criminal accountability largely never materialized. Decades later, a small number of Indian managers were convicted in 2010 of causing death by negligence and received minimal sentences—an outcome that many survivors and observers call grossly inadequate.

Another complicating factor is corporate succession. Dow Chemical acquired Union Carbide in 2001 and has consistently rejected claims that the acquisition transferred liability for Bhopal. Dow’s legal position has been that it did not assume UCC’s historical liabilities for the disaster—a stance that has been challenged politically and in public opinion but has held up in courts. For victims and campaigners, the moral question remains: should a company that now owns the assets and archives of UCC also shoulder responsibility for restitution and cleanup? This remains a live controversy and a focal point for activists.

Comment

Reply