11 Dec 2024

Tired Earth

By The Editorial Board

A group of U.S. and Canadian marine and environmental scientists were amazed to find that some species are thriving on plastic trash floating in the Pacific Ocean.

The team discovered oceanic barnacles and crabs living alongside coastal barnacles and anemones.

“We expected to find oceanic marine species that have adapted on plastics, but we were absolutely surprised to discover coastal marine species as well,” said Linsey Haram, a research associate with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Maryland.

It is not known how some coastal marine life managed to get out into the ocean, added Haram, the lead author of a recent report on the findings in the journal Nature Communications.

“They may already be out there settling on the plastics, but most likely they are being rafted or transported from the coast on floating debris,” she told VOA.

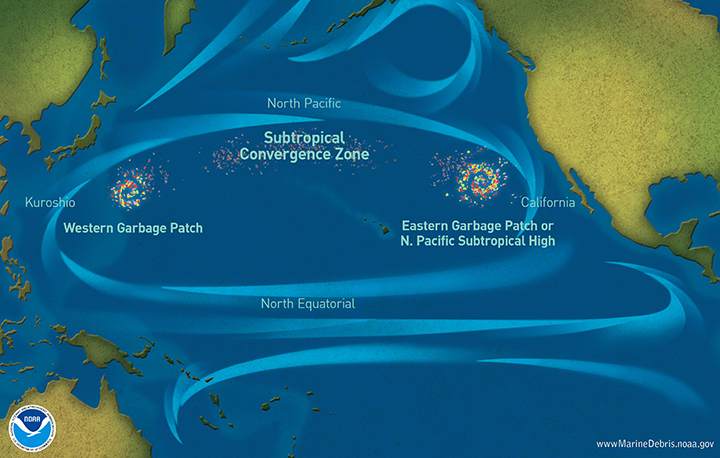

The study focused on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch located between Hawaii and California. The massive garbage patch, which is over 1.5 million square kilometers, is mostly made up of plastic waste, big and small.

The debris includes massive quantities of tiny plastic fragments, along with water bottles, toothbrushes and abandoned fishing gear that are drawn into the patch by ocean currents called gyres.

The report notes the plastic can remain in the gyres for years.

“They come into the center [of the gyres] where the water is relatively stationary,” explained Amy Uhrin, chief scientist of the Marine Debris Program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Washington. The majority of the garbage comes from the Pacific Rim and the West Coast of North America, she said.

The size of the patch can change depending on the wind and ocean currents, Uhrin told VOA in an interview.

The Ocean Voyages Institute in Sausalito, California, which works to clean up trash in the ocean, provided plastic samples for the research.

“We’ve had a large sailing cargo ship with a crane hoist tons of trash from the patch onto the deck of the vessel, especially the very harmful elements like plastic fishing nets that still catch and kill whales, dolphins and turtles,” Ocean Voyages founder and President Mary Crowley said.

The results from the samples provided the researchers with some food for thought.

“What has been most eye-opening is that the coastal marine species were not only thriving but reproducing,” Haram said.

However, there are many questions still unanswered.

“How do you survive being on piece of plastic in the middle of the ocean?” asks Greg Ruiz, a marine ecologist with the Smithsonian’s Environmental Research Center and a contributor to the report.

“The coastal species may be creating their own ecosystem on the plastic debris that allows for microorganisms and algae to grow and essentially function as a food chain,” Ruiz said. “Fish and bird waste in the water may also be contributing nutrients.”

“We also want to figure out how the coastal and oceanic species are interacting since they are competing for limited space on the objects,” Haram said. “They could be using each other as a source of food.”

There is concern coastal hitchhikers could become invasive species.

“We want to know if other coastal marine life are on plastics in all of the five main ocean gyres worldwide,” Haram said.

Ruiz added, “we’re concerned that coastal organisms from different regions could form colonies and spread disease to other marine life, including fish.”

Source : voanews.com

Comment