29 Jan 2026

Tired Earth

By The Editorial Board

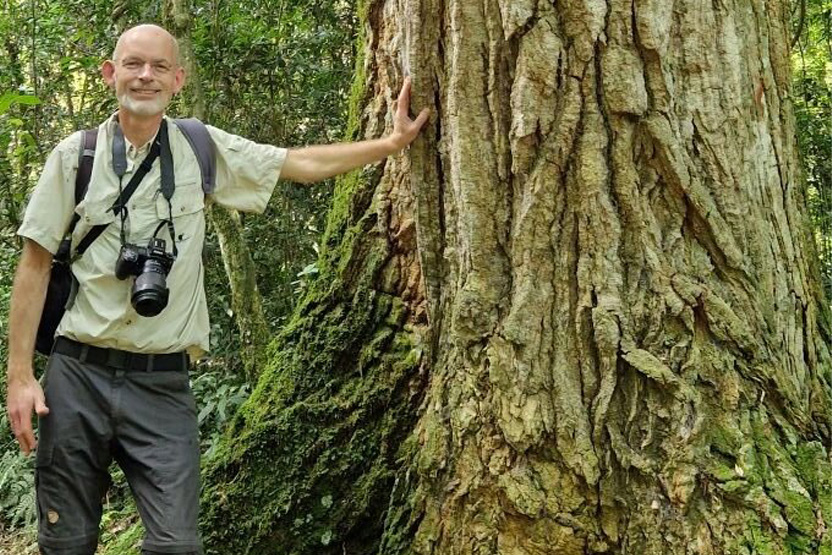

Professor Jens-Christian Svenning with a specimen of the species Aspidosperma polyneuron in Argentina. The tree is an example of one of the "slow" species that are declining despite their high ecological value. Credit: Jens-Christian Svenning

Trees play a central role in life on Earth. They store CO₂, provide habitats for animals, fungi, and insects, stabilize soils, regulate water cycles, and supply resources that humans rely on—from timber and food to recreation and shade on a hot day.

But the world's forests are entering a new era, characterized by homogenization, biodiversity loss, and weakened ecosystems. This is shown by a comprehensive international study published in Nature Plants.

The researchers analyzed more than 31,000 tree species worldwide and provided a global picture of how forests are likely to change—in terms of composition, resilience, and ecological functioning.

According to the study, forests will increasingly be dominated by fast-growing tree types, while slow-growing and more specialized species are at risk of disappearing.

This is a worrying development, according to Jens-Christian Svenning, Professor and Director of the Danish National Research Foundation's Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere (ECONOVO) at the Department of Biology, Aarhus University, and one of the leading authors of the study.

He warns particularly against the loss of tree species that occur only in very limited areas of the world.

"We are talking about highly unique species, especially concentrated in tropical and subtropical regions, where biodiversity is high and ecosystems are tightly interconnected. When specialized, native species disappear, they leave gaps in ecosystems that alien species rarely fill, even if those species are fast-growing and highly dispersive," says Svenning.

Functional and environmental spaces of tree species. Credit: Nature Plants (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41477-025-02207-2

The most threatened species are often slow-growing specialists, as Svenning describes them. These are trees with thick leaves, dense wood, and long lifespans, often associated with stable environments—particularly moist tropical and subtropical forests.

"They form the backbone of forest ecosystems and contribute to stability, carbon storage, and resilience to change," says Svenning.

If current trends in climate change and forest exploitation continue, forests will increasingly be dominated by nature's "sprinters": trees with light leaves and low wood density that allow rapid growth in the short term. Examples include various species of acacia, eucalyptus, poplar, and pine.

"Although these species establish and grow well, they are more vulnerable to drought, storms, pests, and climatic shocks. This makes forests less stable and less effective at storing carbon over the long term," says Svenning.

The study also shows that nearly 41% of so-called naturalized tree species—species that do not naturally occur in a given area but now grow wild there—possess traits such as fast growth and small leaves. This makes them well-suited to disturbed environments, but they rarely perform the same ecological roles as native species, says Svenning.

"Moreover, in landscapes affected by today's and tomorrow's disturbances, naturalized species can make it even harder for native trees to survive, because competition for light, water, and nutrients intensifies," he adds.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights. Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs, innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Forest homogenization hits the tropics and subtropics particularly hard, with future rises in tree species endangerment concentrated in these regions.

"This is where many slow-growing tree species with naturally small ranges occur. Because they are confined to very limited areas, these species are especially vulnerable and risk disappearing entirely if their habitats are destroyed or taken over by fast-growing species," explains the study's first author, young professor Wen-Yong Guo from the School of Ecological and Environmental Sciences, East China Normal University, Shanghai.

"At the same time, we forecast rising number of naturalized and fast-growing tree species adapted to increasing disturbance throughout the world. Hence, in the colder parts of the Northern Hemisphere, the likely dominant dynamic is the invasion of such species," says Wen-Yong Guo.

According to the researchers, human activities are the primary drivers of changes in forest composition.

"Human-driven climate change, deforestation for infrastructure, intensive forestry, logging, and global trade in tree species all play a role. Fast-growing trees are often actively promoted because they produce timber or biomass quickly. But ecologically, they are often fragile and more prone to disease," explains Wen-Yong Guo.

In the study, the researchers modeled how tree species are likely to spread or disappear under future scenarios. The results clearly indicate that already naturalized species are expected to become even more dominant in forests in the coming decades.

This makes it urgent to halt the loss of slow-growing tree species, says Svenning. This can be achieved by giving them greater priority in forest management and through more active ecosystem restoration.

"When establishing new forests, far more emphasis should be placed on slow-growing and rare tree species. This would make forests more diverse and resilient. These species should also be actively promoted in conservation and restoration efforts, where they often interact positively with the recovery of richer communities of large animals, which themselves are also important for future ecosystem functioning," concludes Svenning.

Source : phys.org

Comment