The underpinning strategic logic behind PLAN E is for nations to undertake a pivot in their threat posture, at the level of grand strategy. Coherent grand strategy means that all arms of Government and the nation are aligned in their objectives, and the objectives are worthwhile.

It is timely that Green Agenda consider the issue of hope, because the circumstances humanity and the living planet face in 2021 are dire.

At the time of the Glasgow climate summit, the world finds itself facing three types of security crises:

- Planetary security is threatened by the Climate Emergency; the sixth extinction event; and the precariousness of other planetary boundaries.

- Human security is degrading. Aside from a global pandemic, the human protection regime (institutions and laws to protect human rights and dignity) is in decline, as are levels of democracy and freedom. A wide range of other human security problems are encapsulated by limited progress on most UN Sustainable Development Goals.

- State security faces multivarious pressures. Many states suffer from disproportionate influence upon decision-making by powerful yet non-elected groups. Global militarisation reflects increased expectations of conflict over the 2021 to 2030 period.

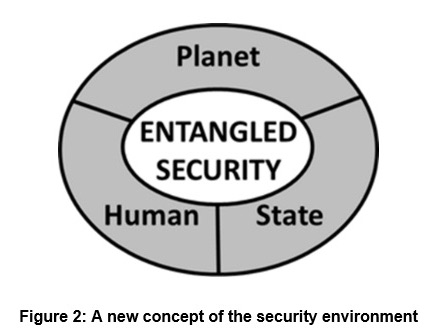

People from these three professional tribes (planetary, human, and state security) do talk to each other, yet each tribe has their own institutions, methods, culture, and objectives – which sometimes conflict. When they interact, it may be adhoc; oriented around a particular disaster or planning scenario; or only involve some sub-tribes, rather than a full spectrum discussion. This is a shame because these three facets of security are integrally connected, and believe it or not, when one confronts them all concurrently, strange new pathways to peace emerge. However, it is not merely the lack of interconnected discourse that is the problem. In my research I found a more significant issue is redundant conceptual approaches to threat and security.

It is in this context that I wish to introduce a new approach, explored in my doctoral thesis which asks Climate and environmental change: is it time to reframe threat? The research developed a new conceptual approach to threat, and a new strategy for peace – which I call PLAN E (and is available in Chapter 14 of the thesis).

The ‘mission’ of PLAN E is to reach ‘Destination Safe Earth’ – (where safe earth refers to a safe climate, and a safe existence for not only humans, but also all forms of life). In other words, this is a security strategy that does not centre humans. Another unique feature is that, while not negating other security or policy concerns, it prioritises addressing global warming – which is assessed as the most dangerous threat. To my knowledge, this is the first climate-centred security strategy in the world.

Risks of a threat framing

As Green Agenda readership will well know, and as articulated in Nick Buxton’s recent critique, The dangers of militarising the climate crisis, there are significant risks associated with ‘securitising’ public policy issues. However, there are also risks when planetary and human security issues are marginalised within national and global security strategy-making. Balancing these two sets of risk is akin to walking an intellectual tightrope. Despite the problems, I found that reticence to seriously consider the ‘threat’ dimensions of climate and environmental change, and how these interact with extant national security strategy, may have one, undermined capacity to understand our full predicament and two, reduced capacity to critique and challenge dominant security framings and strategies.

In this article, I aim to overview the approach and introduce some key terms, however, I will focus upon Australia’s strategic misalignment. While this negative story may seem the antithesis of hope; engaging with this difficult angle offers a security-based argument for change.

Overview of approach

An ex-Army logistics officer, my question was: ‘if’ climate and environmental change does constitute a new form of threat (existential, catastrophic), then could military strategy inform response? In other words, could the prevailing body of work (thousands of years of warfare studies) on ‘how’ to respond to overwhelming, destructive threat, in short time frames, be applied to the planetary security context? The answer that emerged was that traditional threat response planning methods were useful when applied in a careful and modified way; but they were even more useful when fused with new eco-philosophical constructs.

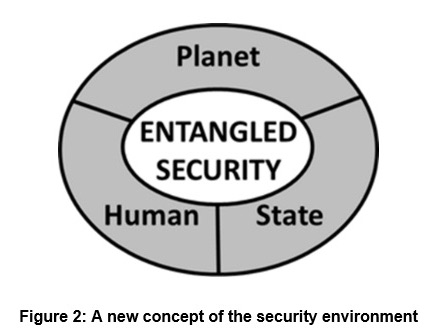

Guided by war theorists like Carl von Clausewitz or Sun Tzu, the first step was developing new concept of threat (the hyperthreat); then developing a conceptual appreciation of the security environment (entangled security), and finally considering how to dilute the hyperthreat, within an entangled security environment (PLAN E).

The hyperthreat frame – what is it?

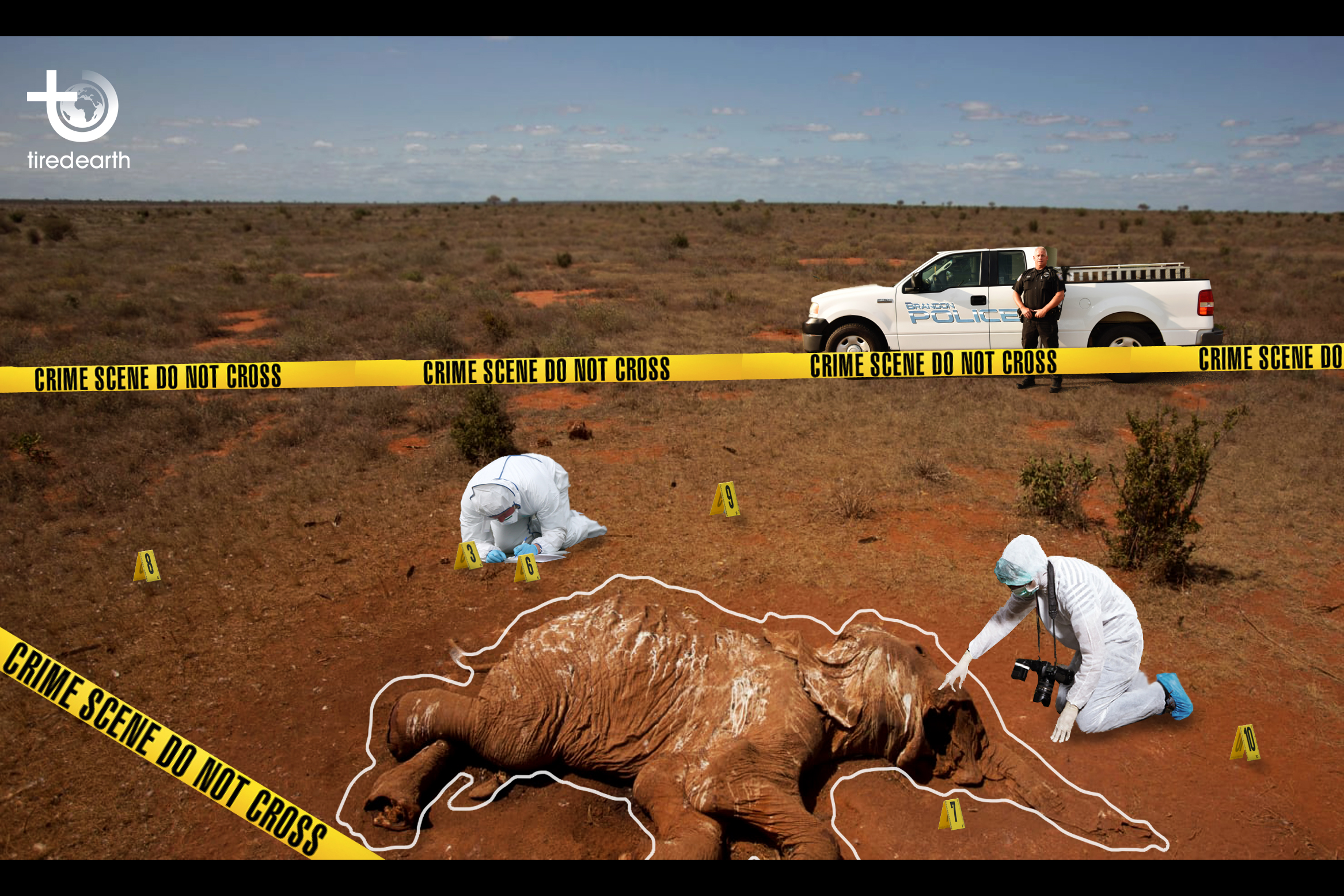

The hyperthreat frame posits that, taken together, global warming and environment decline and destruction are not solely policy issues, but rather constitute a new form of threat (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The hyperthreat of climate and environmental change

While climate crisis or climate emergency frames highlight urgency, hyperthreat spotlights the violence, destruction, killing, harm, and loss of freedoms that are imposed by unravelling ecological and climate systems. This includes the explosive violence associated with extreme weather events, but also what Rob Nixon has described as the ‘slow violence’ associated with degradation of the natural environment.

It draws from Timothy Morton’s concept of global warming as a hyperobject – something beyond human’s capacity to perceive or understand, which utterly defies our current ‘systems.’ Morton argues that, in the face of the hyperobject, humanity’s new existential truth is that we are now “weak, lame and vulnerable.” Morton proposes that in the 21st century, humans have lost agency, that the hyperobject of global warming will be the key actor and shaper of events.

In contrast, the hyperthreat notion, views that humans have still got a chance. If humanity have scaled the problem too small, we can still step up and think at the ‘hyper-scale’ for solutions which transcend extant institutional design.

Critically, ‘the environment’ is not the ‘enemy’ – the ‘threat’ results from the impacts of an acutely stressed environment. Further, it doesn’t regard the climate and environmental crisis, and its associated impacts, as random hazards – caused by uncontrollable events – but rather teases out new forms of complicity or ‘intent to cause harm’ that require far stronger governance measures to address.

Entangled Security – what is it?

In its simplest form, entangled security is a conceptual approach to security that appreciates planetary, human and state security are inherently entangled and inter-connected (Figure 2).

Strategic misalignment

Analysing the hyperthreat in the context of an entangled security environment allows a disturbing picture of strategic incoherence to emerge. Considering recent US and Australian security decision-making helps to illustrate this.

Frog-marching folly

With the deadline for the US withdrawal from Afghanistan set for 31st August 2021, and it becoming increasingly clear that planning for the evacuation of Afghani interpreters and support staff, as well as measures to support the Afghanistan Government, were unravelling, in news coverage, many key US and Australian foreign policy and security officials sought to shift attention to ‘the next campaign.’ In July, Minister for Defence Peter Dutton explained that the Afghanistan defeat was a campaign that had “come to an end”, while alluding to the possibility of pursuing further campaigns with the US and supporting allies. In mid-August, news agencies spotlighted the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command annual Chiefs of Defense conference; involving 19 Indo-Pacific nations, including Australia. In late August, US Vice President Kamala Harris toured South East Asia. On 16th September, the Australian Prime Minister announced the AUKUS alliance stating:

The security challenges in the Indo-Pacific region have grown significantly. Military modernisation is occurring at an unprecedented rate…

Initial efforts under AUKUS will focus on cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and additional undersea capabilities.

This is an historic opportunity for the three nations, with like-minded allies and partners, to protect shared values and promote security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.

Despite muted language, it was clear that China was regarded as the number one threat, and tellingly, only six weeks before COP26, AUKUS did not mention planetary or human security issues. The effect of all of these announcements and activity within the Indo-Pacific was to quickly knee-cap post-mortem analysis of the Middle East strategy. It also robbed the community of the time and space to deeply consider our security posture anew in the context of Middle East failures and the approaching Glasgow talks.

It is worth pondering the significance of this decision-making. One way of looking at what has occurred, is that the US and its allies have just emerged from a disastrous (see the Costs of War project) resource war in the Middle East. Yet before it was even complete, AUKUS Nations seem to be frog-marching into another geopolitical conflict, also with resource dimensions, with seemingly no significant efforts to find an alternative pathway.

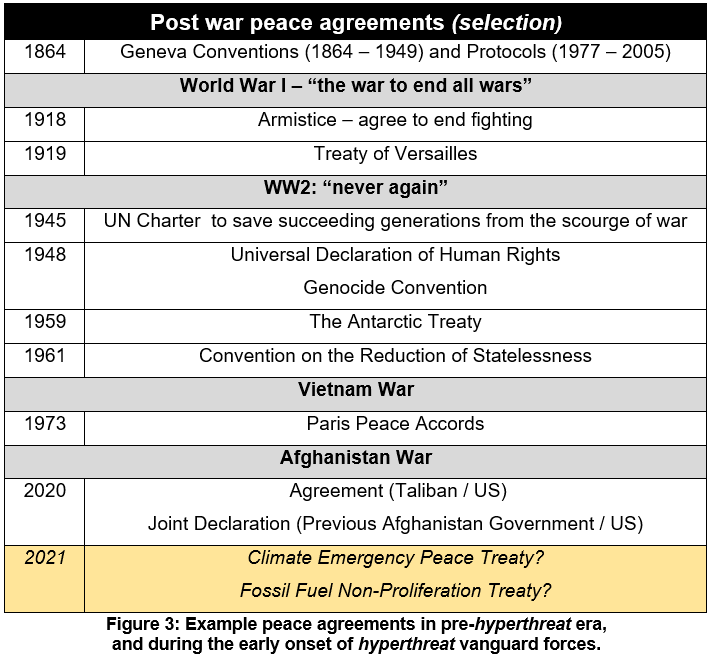

What happened after other major wars?

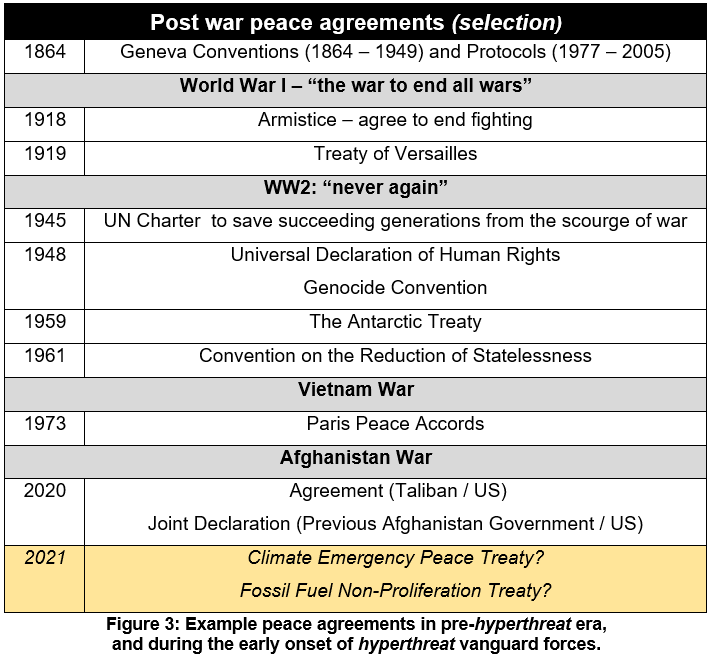

While the Middle East wars were not on the scale of WW1 or WW2, it is still instructive to consider global community response to past wars (Figure 3). Last century, warfare was followed by concerted efforts towards global peace. Sometimes countries who caused war were required to acknowledge fault and pay reparations. War criminals were pursued.

In comparison, while the US/Taliban/Afghanistan Government Agreement and Declarations had positive dimensions, the collective will of the international community, and especially AUKUS nations, don’t appear moved at all by the scale of tragedy in the Middle East. There is no pause, no concerted efforts to find a new way. Rather, militarisation and military spending is accelerating. Given the world is on the cusp of slipping into a dangerous climate change trajectory and confronts the sixth extinction event and wide-ranging human security issues, large-scale warfare, in my view, now would constitute a new type of Mutually Assured Destruction’ (MAD).

A new ‘Mutually Assured Destruction’ (MAD)

The term ‘mutually assured destruction’(MAD) refers to a conflict deterrence strategy mostly associated with Cold War nuclear powers, which rests upon the idea that States will avoid initiating conflict, if the risk of severe retaliation and subsequent destruction is high. ‘MAD’ logic can be applied to warfare in the context of a climate and ecological crisis.

Because of its demand upon fossil fuels; the likelihood of further damage to fragile ecological systems, and the diversion of limited funds and human ingenuity from zero emissions and ecological design pathways, any major conflict over the 2021 to 2030 period will likely derail the chance to achieve a safe climate. Even if only a Cold War or Hot Peace scenario occurs, the costs of participating in an arms race will still drain capacity for transformative responses to planetary and human security challenges.

Now, MAD logic occurs differently. Consider a major WW3 type conflict scenario; even if a State ‘won’ a prospective military confrontation, it would likely still ‘lose’ because the hyperthreat will not have been contained. Rather, due to high fossil fuel use and harm to ecological systems a ‘war winner’ would, most likely, face an enraged and strengthened hyperthreat capable of inflicting even greater levels of killing, harm and destruction. In other words, embarking on major warfare now (posited as being for our ‘security’), could destroy security for all of earth’s inhabitants – because it would prevent curtailing dangerous climate change and ecological collapse.

Don’t mention resource wars

In most analysis of Australian defence activity and security dilemmas, the ‘natural resource’ dimensions are typically only mentioned in passing. The focus is upon weaponry, tactics, capabilities, and intentions. However, as energy-security scholar Jeff Colgan writes, “many international conflicts are in some way related to energy.” Consider these geopolitical conflicts and tensions:

- The Afghanistan/Iraq wars (2001-2021). Jeff Colgan reveals fossil fuel related influences.

- South China Sea. Abundant fisheries; a major fossil fuel thoroughfare; significant fossil fuels reserves.

- Antarctica. Facing military encroachment. Rich in fisheries, fresh water, minerals, including oil, gas, and coal.

While the ‘race for what’s left’ strategy is never overtly named, if resource acquisition objectives underpin future Australian (and other Nations) defence and security strategies, this needs to be made transparent to the public or the ‘global citizen.’ This is because, as eco-design, zero emissions and circular economy experts know, there are other options.

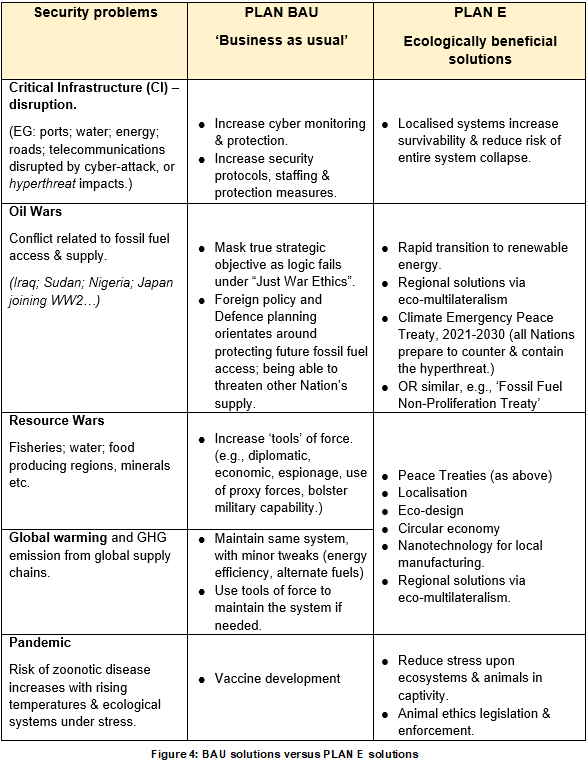

We have other options

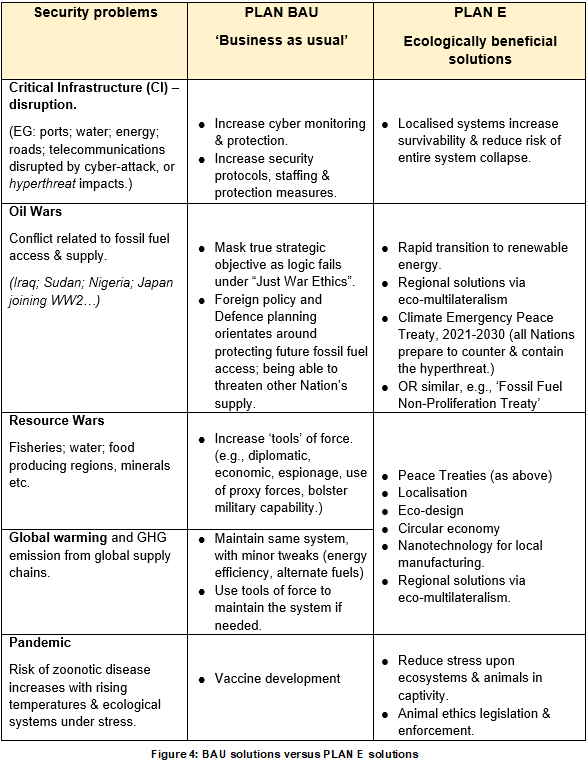

A snap-shot showing how traditional security problems can be addressed in new ways is shown in Figure 4 below. However, what is lacking is an overarching strategic logic which would direct planners to analyse and to apply such new solutions.

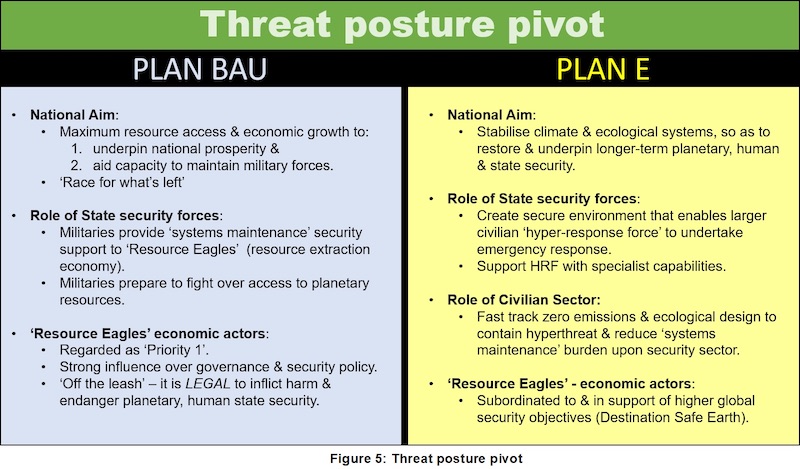

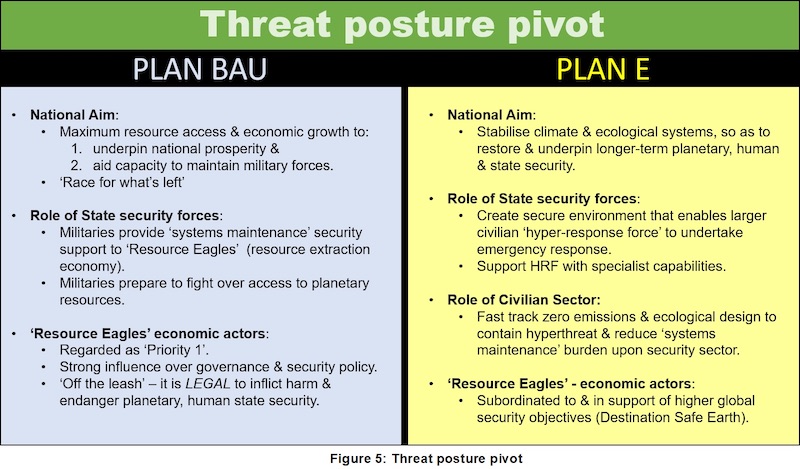

PLAN E: Threat posture pivot

The underpinning strategic logic behind PLAN E is for nations to undertake a pivot in their threat posture, at the level of grand strategy. Coherent grand strategy means that all arms of Government and the nation are aligned in their objectives, and the objectives are worthwhile.

While many nations are producing new ‘climate-security’ considerations within their defence and security policies, these tend to focus upon doing the same thing in a greener way (low emissions fuels etc); adapting to climate-impacts upon the security environment, but not fundamentally shifting their National Whole-of-Government threat posture to slow the hyperthreat’s advancement.

The US DOD’s October 2021 Climate Adaptation Plan uses terms like “climate justice” yet underpinning posture and strategic objectives have not been realigned. For example, one desired strategic outcome is “uninterrupted access to key supplies, materials, chemicals and services”. This is the same ‘resource capture’ objective the US and multi-nationals have pursued so brutally, as described by John Perkins in his various Confessions of an Economic Hitman books. The pivot I am proposing is far more substantial, see Figure 5.

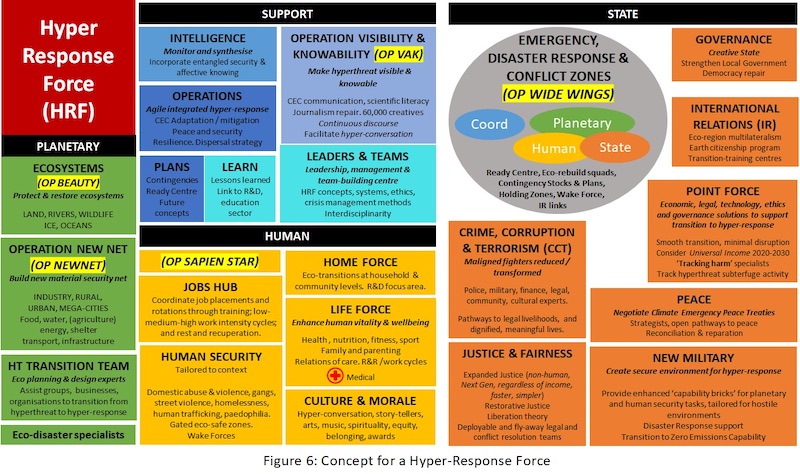

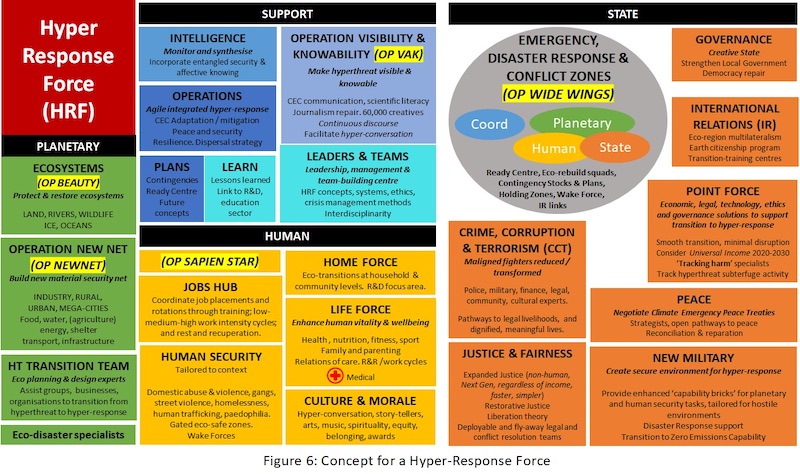

Hyper-response force

The scale of danger imposed by the hyperthreat, and speed and magnitude of response required, leads to a conclusion that a civil mobilisation is required – which is distinct from militarisation. Further, rather than a ‘top-down’ focus, it envisions a far greater devolution of security responsibility to local, regional levels and to the level of design – design of products, urban planning and so on.

To aid the process of imaging what a new climate and environment centred threat posture might look like, Figure 6 below shows an initial concept for a hyper-response force (HRF). The HRF design intends to operationalise entangled security. It is expected to vary according to context. In general terms, it provides orchestration logic (which can be applied at eco-regional, nation-state and local levels), but also involves raising some new capabilities. The HRF is not envisioned as a rigid structure or organisation.

Grand Strategy and choices

Phrases like ‘militarised capitalism’ are simplistic, however, at a broad-brush level, they do describe aspects of how the world’s security sector is employed. The fossil fuel powered industrial era persists partly because it has had and continues to have significant state and military support. If it became a new security imperative to contain the hyperthreat, and instead support a hyper-response, then this would mean that the entire system of the ‘military industrial complex’ and the entire logic of state security strategy would need to undertake an extraordinary pivot. That sort of horse-power could be very helpful – if it was aligned the right way.

If the hyperthreat is permitted to reach its full fighting strength, as the IPCC have warned, much of the living planet will be overwhelmed. The threat environment has utterly changed. Our region is either the tinderbox for WW3 combined with a growing hyperthreat, or it is the place where a new bold vision emerges. While it will be difficult to unwind tensions, with strategic foresight, skill and stamina, neighbouring Nations of the Indo-Pacific region could seed a new era of global peace and cooperation, which leads to extraordinary rehabilitation of earth’s ecological balance – and the taming of the hyperthreat beast.

Australia – from colonial mind-set to leader?

Considering Australia, we have two choices: first, continue the same trajectory and approach of the failed Vietnam and Middle East wars, while also participating in the ‘race for what’s left’ or, second, shift from colonial follower to global leader. Australia could pioneer a new security approach in our region. As our old masters, the UK and US arrive; with Australian possibly slated to be a major base for an era of southern hemisphere conflict, we could step up and offer a new vision:

“We’ve done some thinking…” we’d say, with eyes squinting in the sun and a wry smile. “We followed you to Gallipoli, Vietnam and Iraq. But this time… this time… ah nah mate. Nah. We got a better idea… You see, we like seafood on the barbie. Koalas in our trees. It’s called PLAN E. It’s too easy, you’ll see. Nothing to fear… let me tell you about it over a beer…”

Conclusion

Is it time to reframe threat? I believe it is at least worth opening the discussion to the community, to ascertain what their security priorities are. Reframing threat does not mean a top-down militarised solution. Threat response can be re-imagined so that it matches the nature of the problem, the times and people’s preferences. Humanity has significant latent capacity, locked up in siloed approaches, institutions and structures from another era, which can be reconfigured and refocused. We can raise new capabilities charged with a major rescue operation of our most important, our most essential, our most beloved ally, nature. Nature, the delightful companion to the human species, friend to us always, is presently besieged by multiple threats and will fall soon if we do not act enmasse, with tremendous resolve and unity.

This article was originally published on Green Agenda and appears here with permission.

Comment

Reply