California drought: State Water Project will deliver no water to most communities next year

After two historically dry years, Lake Oroville in Butte County, the second-largest reservoir in California, was at low levels on October 28, 2021. The reservoir was just 30% full on Dec. 1, 2021. (Photo: State Department of Water Resources)

In a stark indicator of California’s worsening drought, the Newsom administration announced Wednesday that cities and farms should expect to receive virtually no water next year from the State Water Project, a massive system of dams, pipes and canals that typically provides water to 27 million people from Silicon Valley to San Diego.

The unprecedented announcement — with only small amounts of emergency supplies possible for some urban areas — means that unless this winter brings significant rainfall, more stringent conservation measures are likely in San Jose, parts of the East Bay and other communities across the state in 2022, including strict limits on landscape watering.

“We’re coming off an historic set of conditions,” said Karla Nemeth, director of the state Department of Water Resources.

Nemeth also said that if significant rainfall does not occur this winter, Gov. Gavin Newsom is likely to impose mandatory urban water conservation targets, similar to those put in place by former Gov. Jerry Brown during California’s last drought from 2012-16.

“We’ll see that probably late winter, early spring if these dry conditions persist,” she said.

This summer, Newsom asked California residents and businesses to reduce urban water use by 15% from last year’s levels. But they are falling far short, cutting by only 3.9% in September.

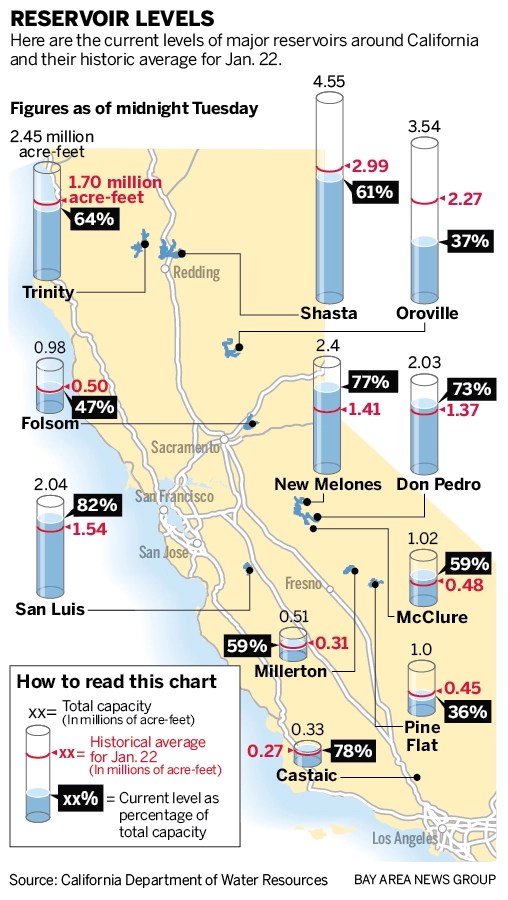

The past two years have been the driest back-to-back years in Northern California since 1976-77, leaving major reservoirs at record-low levels. Lake Oroville, in Butte County, the second-largest reservoir in the state and the largest in the State Water Project, was just 30% full Wednesday.

Even though Northern California received heavy rain in October, much of it soaked into the dry ground instead of running off into reservoirs. Since then, very little rain has fallen.

The State Water Project, approved by voters in 1960 and a key legacy of former Gov. Pat Brown, moves water from Northern California to the south. It takes melting snow from the Sierra Nevada and transports it from Lake Oroville through the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta all the way to the Los Angeles Basin. In normal times, it supplies drinking water to two out of three Californians — and irrigates about 750,000 acres of farmland.

Nemeth said her department is in discussions with seven of the 29 urban and agricultural agencies that contract to receive State Water Project water for them to receive “very modest” amounts of “health and safety” water next summer for fire fighting, hospitals and some indoor uses, including drinking water, toilets, showers and clothes washing, but not for landscape irrigation.

That amount will be 55 gallons per person per day, she said. The state could provide the difference if local water agencies cannot meet that amount, she added. The total the state expects to deliver of such “health and safety” water is 340,000 acre-feet. By comparison, all cities and farm districts have state contracts for 4.2 million acre-feet.

Wednesday’s announcement is the first time since January 2014, during the depths of the last drought, for a 0% allotment, and the first time ever that such an announcement was made in December, at the beginning of winter.

Among the agencies affected by Wednesday’s news are the Santa Clara Valley Water District, in San Jose, which provides drinking water to 2 million South Bay residents. Also hit: Alameda County Water District, which provides water to 360,000 people in Fremont, Newark and Union City; and Zone 7 Water Agency, which serves Livermore, Pleasanton and Dublin.

The news does not affect customers of the East Bay Municipal Utility District, Contra Costa Water District, Marin Municipal Water District or San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, who receive their water from other sources and projects.

Urban areas such as San Jose, Fremont and Livermore, along with Los Angeles and Napa, will have to find other water sources, including local reservoirs, groundwater, more conservation and purchases from farm agencies to get through next year. And many farmers will have to pump more groundwater or fallow fields.

“With the conditions we’ve been seeing, and the reservoir levels where they are, I don’t think we are surprised,” said Aaron Baker, a chief operating officer with the Santa Clara Valley Water District. “It is symbolic of the dry, warmer conditions we are in.”

Baker said the Santa Clara Valley Water District will use local groundwater, conservation and purchases from farm agencies in the Sacramento Valley with senior water rights to avoid severe shortages. Its 10 local reservoirs are only 11% full now.

This summer, the district asked Santa Clara County residents to cut water use 15% from 2019 levels to preserve supplies. So far, they have reduced by only 7%.

Baker said that if it doesn’t rain significantly this winter, Santa Clara County residents should expect more stringent water conservation rules next summer.

On Wednesday, the Marin Municipal Water District, which serves 190,000 people in Marin County, prohibited all outdoor landscape watering seven days a week, with fines for violators. Healdsburg, in Sonoma County, has had similar rules in place for months.

“We need local leaders to step up and make those decisions,” Nemeth said. “If they won’t, the state will.”

The California Aqueduct in Alameda County just north of the Bethany Reservoir and 1.5 miles south of the Harvey O. Banks Pumping Plant, shown here in 2013. (Photo: John Chacon / California Department of Water Resources)